Mopar Max Magazine Article on the P-67 LoadLeash Engine Brake

Pacbrake LoadLeash P-67, Double Down Engine Brake for RAM Cummins Trucks

Words and photos by Richard Kratz Illustration courtesy of Pacbrake

It was 25 years ago that the first RAM truck with a Cummins diesel engine was introduced to the world. A lot has transpired in those 25 years, not the least of which is the ever upwardly spiraling horsepower wars between the domestic auto manufacturers. In 1989, the RAM Cummins came with 160 horsepower and 400 lb. ft. of torque. Our 2014 RAM Cummins 3500 crew cab dually came from the factory with 385 hp and 850 lb. ft. of torque. The tow rating of a 1990 RAM truck with a Cummins engine was a few hundred pounds over 10,000. Our 2014 Project Hard Working Hauler truck is rated for towing 27,000 pounds. If we had opted for the 4.10 rear end gear the rating would have been 30,000 pounds.

Our truck weighs about 9,500 pounds with 85 gallons of fuel onboard (extra capacity thanks to Titan Fuel tanks), two people and a bit of luggage. If we had the 4.10 gears at full trailer rating we’re talking about a straight-off-the-showroom-floor consumer truck and trailer rig rolling down the highway at 39,500 pounds. We’re talking 50% of the maximum gross for a big rig over the road truck and trailer—serious weight and serious hauling. The combined gross weight of the original 1989 RAM Cummins was 16,000 pounds.

There are a lot of things that have contributed to the increase in payload/tow ratings over the years. Our 2014 truck is significantly stronger and beefier in every respect compared to the 1989 version. Empty, our late model truck weighs over 8,000 pounds from the factory—the 1989 version was over 5,000 pounds. A lot of that weight is in larger and more robust frame, suspension, transmission and rear end parts. But adding 3,000 pounds to the diesel RAM over the years has been more than matched by the prodigious increases in power.

We use our truck for hauling and towing and it excels in this role. Fully loaded with our 40’ gooseneck race trailer with the 4,000 pound Maulin’ Magnum race car inside along with tools, pit gear, water tanks and generator fuel tanks all filled up, we’re driving down the road with 26,700 pounds of combined gross weight. The amazing thing about our RAM truck is that it hardly notices the load. Only up the steepest grades do you have to do a little thinking ahead when planning a passing maneuver. Even up 6% grades we have no trouble maintaining the speed limit on any highway. So there’s plenty of “Go” power on tap at all times.

But, what about “Whoa” power? What accelerates must decelerate. The marvelous Cummins engine accelerates our rig, but what about the engine that decelerates it? We know, you normally don’t think of your brakes as an engine, but technically, they are. Your brakes are an engine that converts mechanical energy into thermal energy (heat) that is then transferred into the atmosphere by convection into the air flowing over the brake rotors. Typically, the brakes on a vehicle are much more powerful than the engine under the hood.

We have a good friend, the promoter of some of our favorite races in fact, who has a wife and young child. We saw them at March Meet at Famoso a couple of years ago. They had their diesel one-ton dually and 53’ merchandise/living quarters trailer with them. They were getting ready to head out to Denver after the Meet, which meant they were about to encounter a lot of steep grades. Just as our friend was about to get into their truck, for some reason he happened to look at the front wheel. Something looked a little odd and caught his attention. He looked closer and saw a large crack in the front brake rotor. His left front rotor was on the verge of complete failure. What would have happened if hadn’t glanced at the wheel as he entered his truck? When was the failure going to occur? The worst case scenario of course would have been on one of the many long downhill grades between California and Denver. We shudder to think of what could have happened.

Now, as much as we love our friend, we think he drives the wrong truck. It’s not a RAM. And it doesn’t have any kind of supplemental braking, just normal service brakes on the truck and trailer. Have you ever seen a big rig going down a steep grade with smoke pouring out of the wheels from dangerously overheated brakes? We have, many times. Ever seen a big rig with the brakes on fire? It’s not pretty. In the last year we’ve driven past the scene of two trailer rigs that were just smoldering, melted aluminum on the side of the highway. Brake failure happens, and the more you weigh and tow and haul, the more you stress your service brakes, the more likely you are to be the one with the smoking, burning brakes.

RAM pioneered factory supplement braking when it introduced the new 6.7L Cummins in its 2007 line of heavy duty trucks. If you own a 2007+ RAM Cummins truck, you have a big safety advantage courtesy of RAM innovation. If you own another brand of diesel (heaven forbid!) or a pre-2007 Cummins, then you are wholly reliant on your mechanical service brakes.

Why does this matter, what is supplemental braking? Everyone is familiar with “engine braking,” that feeling of deceleration that you get when your vehicle is in gear and you’ve lifted off the throttle. You can feel your vehicle being slowed by the engine, you can feel the deceleration and you can tell that you’re not just coasting. Engine braking occurs when the resistance within an engine is used to slow a vehicle down, as opposed to using external braking by the friction based service brakes. The advantage to engine braking is that you are decelerating without generating heat and wear on your service brakes.

It’s important to note here the difference between “engine braking” and “exhaust braking.” 2007 and newer RAM Cummins trucks come with factory exhaust brakes. An exhaust brake is, to put it at its most basic level, a potato stuffed up the exhaust pipe. An exhaust brake partially blocks the exhaust path of an engine and therefore increases the resistance within the engine and thus increases the “engine braking” effect.

If you don’t have a factory exhaust brake, you can buy aftermarket ones. These are usually a butterfly valve (think throttle body or carburetor valve) that is activated by electronics and/or vacuum. Under deceleration the valve closes and creates a big increase in exhaust backpressure and allows the engine to work as a braking device.

Factory exhaust brakes, like the one found on our truck, utilize the variable geometry turbo (VGT) to partially block the exhaust path. Since 2007, all Cummins powered RAM trucks have turbochargers with variable geometry of the exhaust turbine blades. This overcomes some of the inherent weaknesses in turbocharger systems, where a large turbo is great for horsepower at higher RPM but suffers at lower rpm/load and conversely a small turbo spools up really quickly for good response at low RPM but runs out of breath and power at higher RPM. Utilizing variable vane technology, manufacturers can provide the best of both worlds in one turbo; it can act like a small turbo at low RPM and a large turbo at high load and RPM.

RAM engineers endowed the latest generation of their diesel trucks with a two-mode exhaust brake. When activated it has an “Auto” and a “Full” mode. It’s kind of interesting to watch the vehicle data display on our dash when the exhaust brake is in use. This display shows you how many pounds of boost you’re making under load (up to 29 pounds from the factory) as well as how many “braking horsepower” you’re generating under deceleration (up to 150 horsepower of braking effect). In Full mode, when you lift off the throttle and the truck begins to decelerate you can watch the “braking meter” of the turbo’s exhaust go right to 150 hp. In Auto mode, the truck’s computers apply anywhere from zero to 150 hp of braking. The auto mode is very effective and is our default mode whenever we’re towing and hauling under normal conditions.

A factory exhaust brake works during the exhaust cycle of the engine. And since the exhaust cycle is only one of four cycles that means that 25% of the time you are experiencing the beneficial effects of exhaust braking when it’s in use. That’s great, but you can do better.

Have you ever heard a big rig going down a steep grade with a deep, staccato noise coming out of its exhaust? That’s the sound of a true engine brake, sometimes called a “Jake” brake (because it was introduced by Jacobs Manufacturing). A true engine brake controls the exhaust valve separately from the normal operation cycle of the camshaft to open the exhaust valve on both the exhaust and the compression strokes of each cylinder. In theory, this increases the effectiveness of the exhaust brake by 100%. In practice, it’s a bit less due to some efficiency losses, but let’s just say it almost doubles your exhaust braking.

Interesting side note, the “Jake” brake was actually invented by Clessie Cummins—Mr. Cummins himself. He had sold his company by the time he invented the engine brake, but tried to sell the idea to Cummins anyway. The company unwisely turned him down. Mr. Cummins had a nephew who was married to the daughter of an executive at Jacobs Manufacturing and that is why we now have “Jake” brakes instead of “Cummins” brakes.

After seeing our friend’s cracked brake rotor for ourselves, and having had some experience towing our trailer back from Denver, we were very interested when we heard of Pacbrake’s new LoadLeash P-67 engine braking system for Cummins engines. Pacbrake is not a Johnny-come-lately company. They’ve been around for over 50 years and make products for on-highway trucks & buses, military, agriculture and construction, oil and gas, and marine industry customers. Pacbrake is a validated supplier for 20+ OEMs and is directly connected to over 3,000 VOEM truck dealers, engine company dealers and independent repair shops that are located across the globe. We knew going into this test that this was a solidly engineered system with OEM level manufacturing quality and testing behind it.

Not to get confusing, but there are a few different approaches to engine brake design and production. Big rigs usually use a compression release brake, which times the opening of the exhaust valve at the top of the compression and exhaust stroke. This forces the engine to work to compress the air in the cylinder, but then releases the pressure before it can act as an air spring and put energy into pushing the piston back down. This system does not require an exhaust brake.

Another approach is a “Bleeder” brake (also called a “Weeper” brake). This system uses a solenoid to hold the exhaust valve open continuously through all four combustion cycles. A bleeder brake requires an exhaust brake in order to function—since the valve is open all of the time there is no compression in the cylinder, the pressure has to be built in the exhaust. The Pacbrake LoadLeash is a bleeder type system. It’s ideal for “small” engines like our 6.7L Cummins.

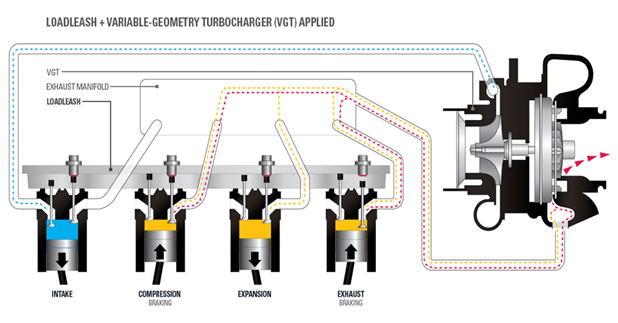

Pacbrake’s LoadLeash for Cummins 6.7L engines is a “weeper” or “bleeder” type engine brake which works in tandem with the vehicle’s variable geometry turbo (VGT) exhaust brake. It functions by slightly holding the exhaust valves off the seat during the complete engine cycle with the VGT providing exhaust backpressure and increased boost pressure. (Image courtesy Pacbrake)

Two braking cycles are achieved.

The first braking cycle is accomplished during the exhaust stroke when the piston is pushing the cylinder pressure past the open exhaust valve against the “closed” VGT.

The second braking cycle occurs during the compression stroke when the piston is pushing the cylinder pressure past the open exhaust valve against the “closed” VGT.

The expansion stroke is eliminated by the open exhaust valve. With work being done on both the compression stroke and the exhaust stroke, we are now doing retarding work on two engine cycles.

So, how hard is it to install and how well does it work? We took our truck to Redlands Truck and RV in Redlands, California for the install. Redlands Truck is an authorized dealer and installer for Pacbrake. Since we are dealing with critical engine valve train parts we wanted to make sure the install was done correctly and safely. (See sidebar on Redlands Truck and RV.)

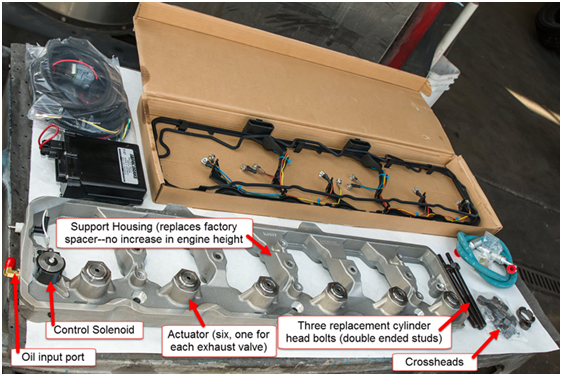

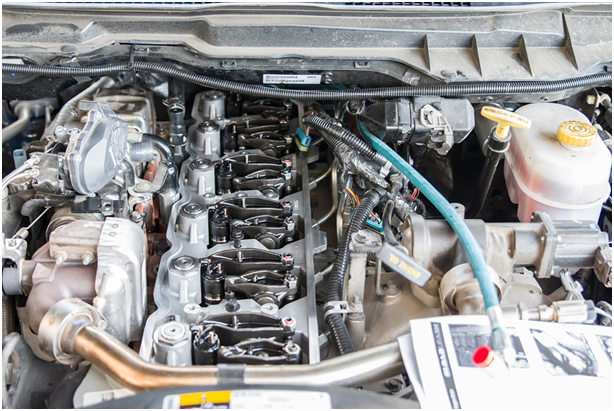

The Pacbrake LoadLeash P-67 engine brake system kit is very complete and well engineered. The aluminum support housing replaces the factory valve cover spacer and contains the oil passages, control solenoid, and actuators for each exhaust valve. The kit also includes an electronic controller, valve cover gasket with integrated wiring harness, Crossheads (valve actuator fingers), oil lines and hardware. Note the three cylinder head studs. These replace three of the engine’s cylinder head bolts and are double ended studs. The studs on the top allow the support housing to be securely bolted down on the actuator side of the housing.

First order of business is to get access to the top of the cylinder head. The gasket/wiring harness will be replaced with the new Pacbrake unit. This is not a project for the novice do-it-yourself mechanic. If you’re comfortable with jobs such as cylinder head replacement on diesels, then you can do this yourself. If not, we highly recommend an authorized Pacbrake dealer install it for you.

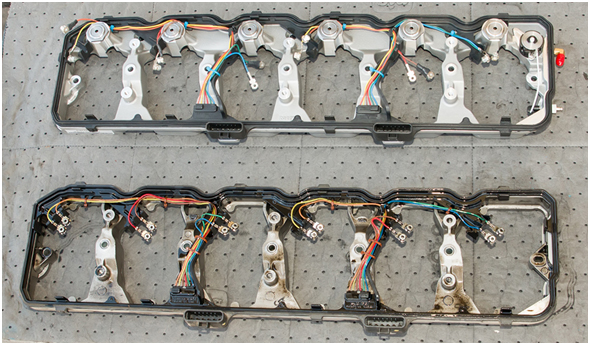

Here you can see the factory spacer and gasket/injector harness on the bottom, and on top you can see the new LoadLeash P-67 support housing with control solenoid, actuators and gasket/harness. Note the brass fitting (here with red rubber cap on it) on the rear of the LoadLeash support housing. The system uses engine oil pressure as a hydraulic fluid, when the control solenoid is opened by the LoadLeash electronic controller, oil flows to the actuators which then depress the exhaust valves holding them slightly open. It is a bit tricky to plumb this up, there’s not a lot of room at the back/top of the engine and you have to ensure all connections are correct and snug—oil leaks are the drips.

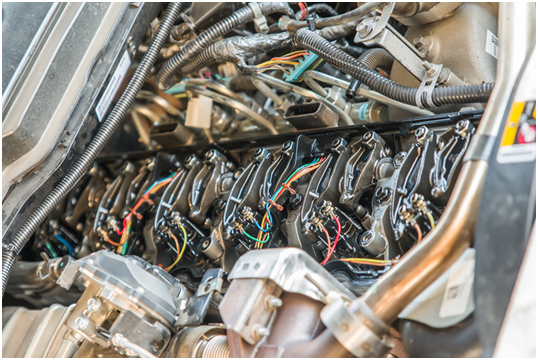

Here’s the LoadLeash system installed and ready for the valve cover gasket with integrated wiring harness to be put into place and the connections made. Note that the LoadLeash system replaces the factory exhaust crossheads, which requires the pushrods to be removed, the crossheads replaced, then upon reassembly the valve lash must be set for each exhaust valve.

Redlands Truck mounted the LoadLeash activation switch on the dash panel to the left of the steering wheel. It’s a convenient place for it and is unobtrusive. Note that Pacbrake says that you must use this switch; you must not substitute a different switch. Apparently this switch is used for diagnostic purposes in the event service is required for the LoadLeash system.

Redlands Truck mounted the electronic controller on the driver’s side as shown. Note the nice aluminum mounting bracket. The bracket is a Pacbrake part, but it’s not part of the LoadLeash P-67 kit. Redlands uses this bracket because they prefer to solidly mount the controller rather than just zip tie it to something.

The installation of the LoadLeash P-67 system took Redlands Truck and RV about a day-and-a-half. Now it was time to see how the system worked. We have both subjective and objective data on this. Subjectively, we can really feel the difference when towing with the LoadLeash system activated. The factory exhaust brake is noticeable by itself, especially when you’re in Tow/Haul mode as the brake seems more aggressive about engaging in this mode. But when we activated the LoadLeash we could really feel the difference, we really don’t need to use the regular friction brakes much with the LoadLeash engaged.

One of the things we like is that the LoadLeash works well with the factory “Auto” setting on the exhaust brake, still providing variable but increased exhaust braking. We use this setting by default whenever we’re towing. We may be on flat and level ground, but you never know when some idiot is going to cut you off, or some hazard is going to appear in front of you. We had a strange incident before the LoadLeash was installed where we were towing our trailer empty (so it was 4,000 pounds lighter than usual). We’re not sure why, but a couple inside an older car decided to slam on their brakes and come to halt in the middle of the 210 Freeway westbound one dark night. There was a cargo van in front of us and traffic was light and flowing well. Suddenly, the van in front of us began braking frantically. We couldn’t see in front of the van, but we began braking hard as well—brake to the floor and letting the ABS do its thing. There were vehicles to our left and right, so swinging around the van wasn’t an option. We came to a stop no more than two feet from the rear bumper of the van.

Our point here is that little things help a lot in emergency situations. In this case, if we’d had the added 4,000 pounds of the race car inside we probably would have hit the van. Similarly, with the factory exhaust brake and LoadLeash activated, in the event of another emergency the added engine braking could be the difference between a close call and a bad outcome.

Objectively, we designed a test to measure the effectiveness of the factory exhaust brake by itself and working in conjunction with the LoadLeash as well as no exhaust braking at all. We live near the infamous “Grapevine” grade on Interstate-5 going over the Tejon pass from Southern California to the San Joaquin Valley. At the top of the grade near Lebec to Grapevine at the bottom, a distance of five miles, this 6% grade plunges from well over 4,000 feet to about 900 feet. It’s steep, really steep. There are at least three runaway truck ramps in that five miles, located on both the left and right side of the highway. Great place to test engine braking, we thought.

Our test protocol was to start at the top of the grade at 55 MPH and allow the truck and trailer to coast down the grade. Every time the vehicle reached 65 MPH, we braked quickly back down to 55 MPH. We would do this test with the LoadLeash system engaged, just the factory exhaust brake engaged, and no exhaust brake at all (to simulate what pre-2007 RAM owners have to deal with.) At the bottom of the grade we’d measure the temperature of the front brake rotor with a laser temperature probe.

We weighed the truck and trailer on a certified scale before the start of the test and our rig weighed 26,740 pounds, well below the maximum combined gross weight rating. We began the test with the LoadLeash engaged and the factory exhaust brake set to “Full” braking mode. Plunging down the grade, well, really moseying down the grade because with everything engaged our rig just didn’t want to accelerate, we only had to apply the service brakes one time, about one-third of the way down. After that, the vehicle just didn’t want to accelerate and we made it the rest of the way down the grade without ever getting near 65 MPH again. At the bottom of the grade at the first off-ramp we came to a stop on the shoulder of the ramp and took a laser temp reading. The front rotor was a cool 205(F) degrees. This is what you’d expect after bringing a 26,000+ pound rig to stop.

Next up, we repeated the test with the LoadLeash disengaged and the factory exhaust brake set to “Full” mode. This time the results were a little different, we had to apply the service brakes three times and the front brake rotors were 325(F) degrees at the bottom.

Finally, everything shut off, just the regular, friction service brakes for keeping speed in check. All we can say is, we don’t want to have to do this ever again. We had to apply the brakes eleven times on the way down. When we came to a stop at the bottom, the brakes were faded and didn’t want to bring the rig to a stop. When we stepped out of the truck smoke was pouring off the front brakes and the front rotors were frying hot at 647(F) degrees.

The results of our test are pretty clear. Any exhaust brake is better than no exhaust brake at all by a huge margin. If you have a diesel rig and you tow or haul with it, you should install an aftermarket exhaust brake. We’ve seen Pacbrake’s exhaust brake and it looks good, and there are other brands out there. But get one, soon, if you don’t have one now. The torture that the service brakes went through with no exhaust braking would not only wear out the brakes very quickly given where we tow here in the mountains out west, but also would make us lose sleep at night worrying about brake failure.

The factory exhaust brake is a big step up. It obviously helped a lot compared to no engine/exhaust brake at all. Still, there is room for improvement. And that improvement is the Pacbrake LoadLeash P-67 system. After testing it for ourselves, we believe their claim that the system can reduce your friction brake wear by 300%. Even down the unusually steep Grapevine grade, our rig just didn’t want to accelerate—there was no fear of the vehicle running away or getting out of control. We think we could have made down from the top of Mt. Everest without any drama, it worked that well.

At the temperatures and the number of applications we saw with the factory brake alone and then working with the LoadLeash system, we have to put the LoadLeash into that category of products that we test where once you use them, you can’t imagine living without them. We know we’ll save money on brake jobs, so that will earn a nice ROI on the LoadLeash system just by itself. But how do you measure ROI on peace of mind? Or on accidents avoided? We just know that we feel far more secure and safe with the LoadLeash than we do without it. Our friend with the cracked rotor knows just what we mean.